But De-Hui Zeng, an ecologist at Liaoning’s Chinese Academy of Sciences, who is studying the substance, says his research squares up with Hepenstrick’s. The Chinese government has strengthened laws around mining to reduce its environmental impact and proposed remediation. According to Climbing Magazine, more than 70 percent of the world’s supply comes from mines in China’s Liaoning Province, where satellite photos show magnesium carbonate powder piled up, and resembling snow, around one mining and processing plant. Magnesium carbonate (MgCO3) is processed from magnesite, a mineral buried deep within the Earth. ( Learn more about the history of rock climbing.) Compounding the problemĪdding to climbing chalk’s potentially problematic nature is how it’s sourced. “When you face a problem on a rock, what do you do?” he says. But more likely it’s a psychological aid. Some climbers may find it helpful, says Daniel Hepenstrick, a co-author of the 2020 study and a doctoral candidate at ETH Zürich. Some papers found no additional grip benefits, while others found the opposite. It’s not even clear whether chalk improves climbing performance at all. As such, they may hold information about that era and how these plants travel. These erratic boulders-rocks scattered across the globe by glaciers at the end of the Ice Age-are islands of vegetation, different from the land they sit on. That matters because some climbing spots, such as erratic boulders (the study’s focus), host unique ecosystems. Wiping it off doesn’t seem to help chemical trails on cleaned boulders changed the rock surface’s pH balance, which could affect the ability of plants to grow there in the future. The latest study on the effects of climbing chalk, released October 2020, found that it negatively impacted both the germination and survival of four species each of rock-dwelling ferns and mosses in laboratory settings. Unauthorized use is prohibited.īeyond the visual pollution, new research suggests chalk may be harming the flora that grows on rocks. Native American tribes have declared areas under Indigenous control off-limits to climbers, not only because of unsightly chalk marks but also to preserve spiritually important areas. Utah’s Arches National Park allows only colored chalk that mostly matches rocks, while Colorado’s Garden of the Gods National Natural Landmark banned all chalk and chalk substitutes. The resulting “chalk graffiti” has become so bad in the United States that parks are beginning to restrict its use.

#Climbing chalk professional#

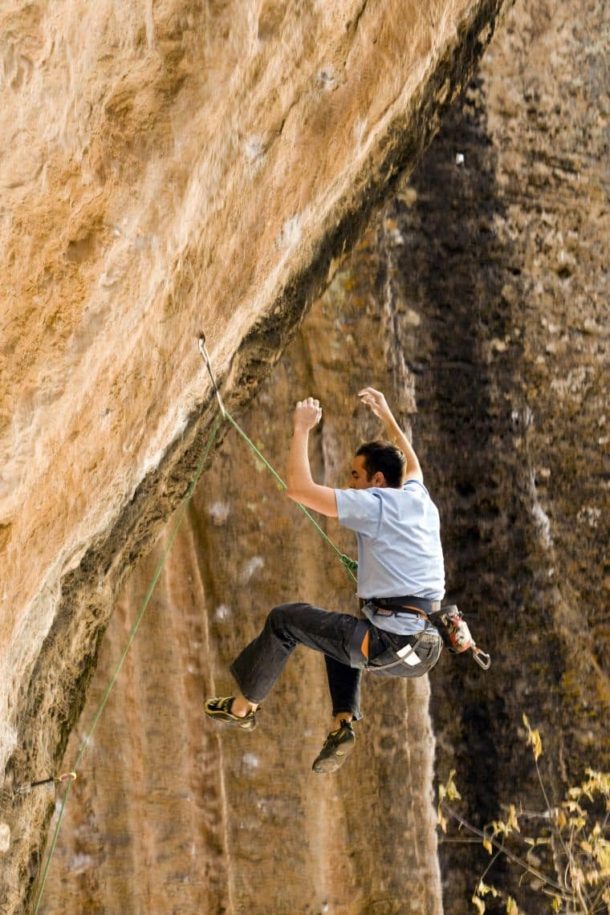

Since then, amateur and professional climbers alike have come to depend on the chalk’s desiccating and friction-inducing properties-and have been leaving streaks of the stuff on rock faces around the world. In fact, it was first introduced to rock climbing in the 1950s by John Gill, who was a gymnast in college before he turned his attention to bouldering.

Made from magnesium carbonate, climbing chalk is the same substance that gymnasts and weightlifters use to improve their grip on bars and weights. Yet the popularity of rock climbing and its sister sport, bouldering (where climbers scramble up large rocks without the use of ropes or harnesses), is raising questions about the damaging environmental effects of climbing chalk-a ubiquitous and essential climbing tool. Now, with its debut at this year’s Tokyo Olympics, the once niche sport is set to reach new heights. Even before climbing star Alex Honnold’s stunning “free solo” ascent of Yosemite’s El Capitan in 2017, rock climbing was gaining a foothold.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)